tl;dr

An unpopular Labour party, led by an unpopular Keir Starmer achieved a landslide victory due to the even more extreme unpopularity of the Conservatives and Rishi Sunak. But this meant that Labour’s victory was on historically low vote share and turnout.

We explore the ways in which this election is exceptional and the ways in which the result is expected given the two leaders’ approval ratings.

We conclude that this result is a lot closer to Labour’s 2005 victory than 1997 and that a competent Tory party would have a very good chance of turning things around over the next five years.

One Thousand Voters at the 2024 Election

How the British electorate voted in 2024 (per 1000 eligible voters).

The above chart shows the 2024 election result (boxes) and the major vote flows (arrows) between 2019 and 2024 (estimated using polling data).

The Conservatives haemorrhaged votes to Reform, Labour and the Lib Dems as well to non-voting. But notably, Labour lost votes compared to 2019, as incoming votes from the Conservatives were smaller than outgoing votes to the Greens, other parties and non-voting. Indeed 80% of the electorate, or 800 voters in our 1000 voter model, did not vote for Labour.

Lowest Winning Vote Share Ever

In fact, Labour won their 174 seat majority with a vote share of just 33.7% on a turnout of 59.9%. A landslide win of the order of 1997 but with:

- The lowest vote share a majority government has ever received

- Only a 1.6% increase on Jeremy Corbyn’s 2019 vote share

- 500,000 fewer votes than in 2019

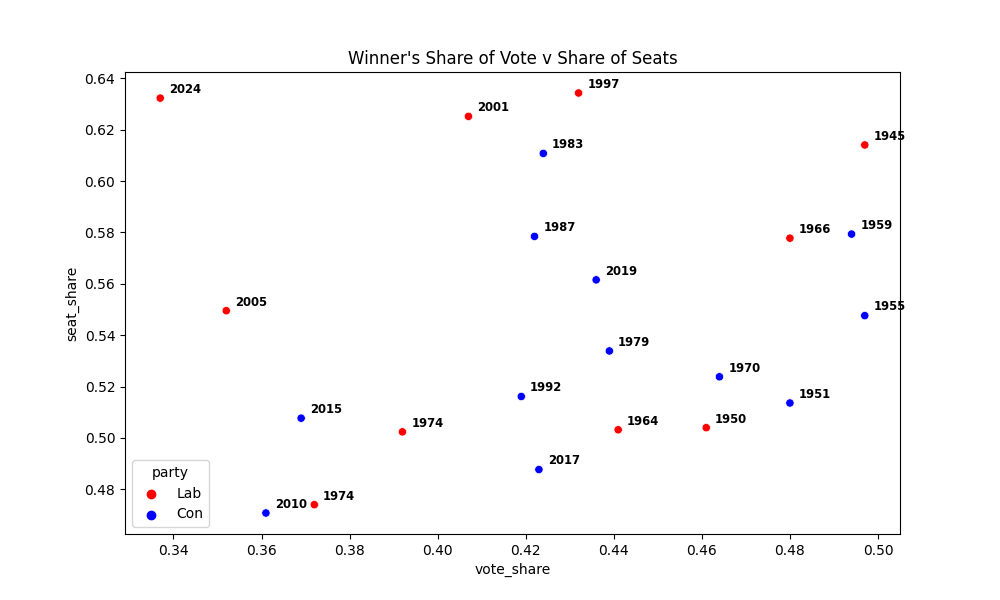

Labour’s result, 63% of the seats on 34% of the vote is an outlier compared to other post war election results.

But share of the vote is not a particularly good predictor of seat share (equivalent to majority size). Excluding 2024, vote share is only 35% correlated with seat share (including 2024 this goes down to 15%).

The difference in vote share between the top two parties (how much more of the vote the winner got than the runner up) is a much better predictor of seat share (75% correlated). On this measure (Labour beating the Conservatives by 10 percentage points) the 2024 result was not atypical, and we can see that the difference was historically high.

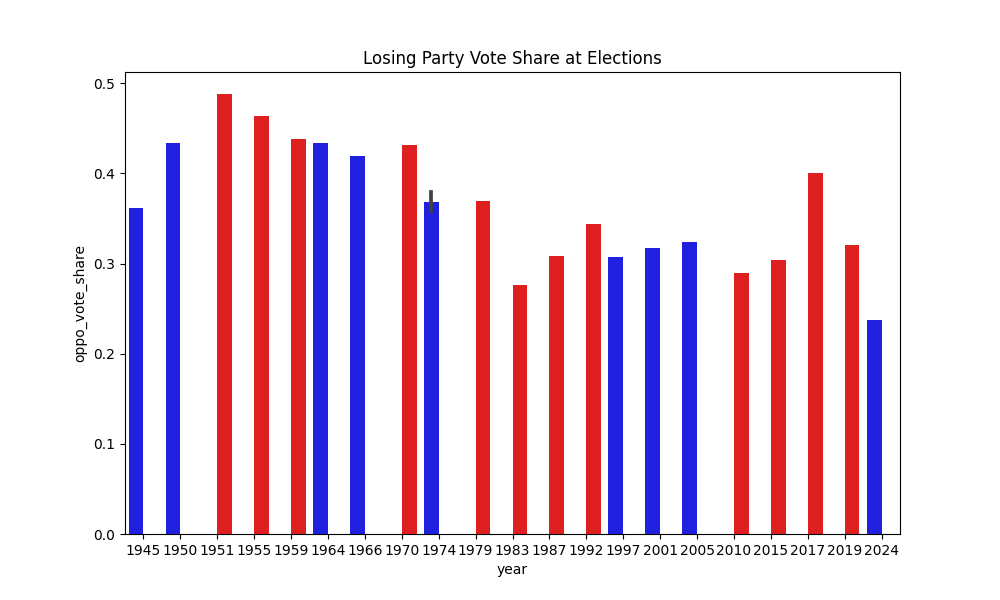

Conservative Collapse

With an underwhelming vote share achieved by Labour, the large gap between the parties was driven by the unprecedented unpopularity of the Conservatives with only 24% of the vote.

And an approval rating for Rishi Sunak of -55%.

Both historic lows. Indeed the government’s approval rating was -71%.

Starmer – the least unpopular option

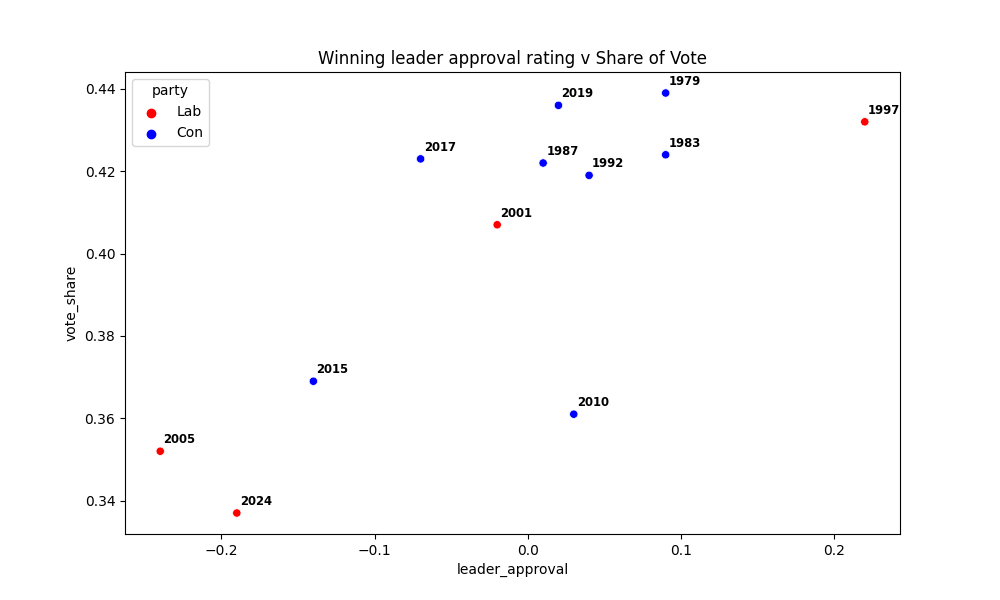

So with a historically unpopular Conservative party, why did Labour not get more votes? Approval ratings of party leaders are highly correlated with party vote share (70%).

Starmer’s approval rating of -19% was the second lowest for an incoming prime minister from Ipsos Mori’s leader approval ratings. Second only to post-Iraq Blair.

In fact, in YouGov’s politician popularity tracker, Starmer comes in at 24th, between John Prescott and William Hague and with the same popularity score (22%) as Jeremy Corbyn. He is less popular than Tony Blair (23%), Theresa May (23%), Angela Rayner (25%) and many more.

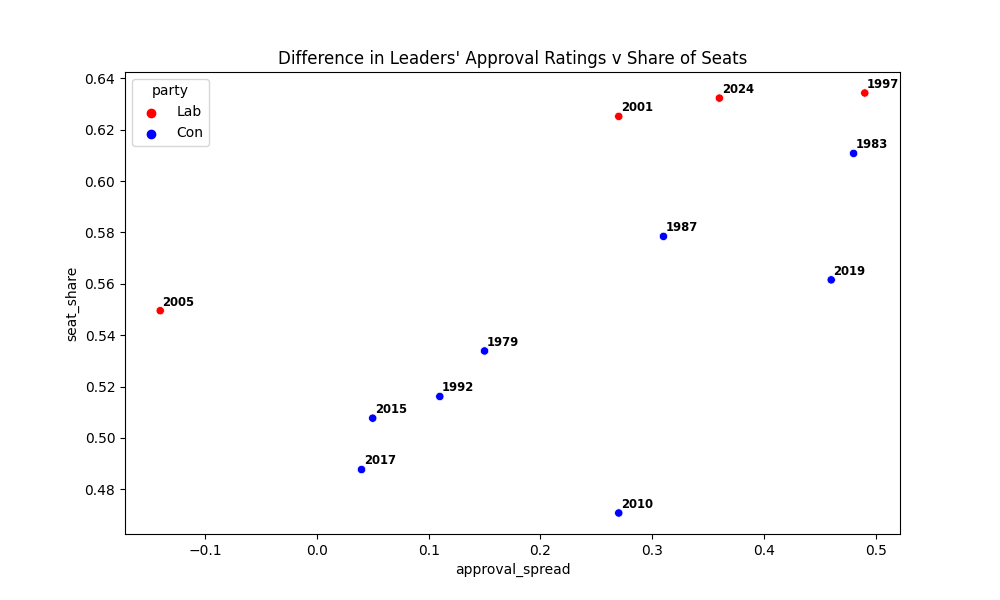

But when comapred to Sunak’s approval rating (-55%), it gives Starmer a relative lead of 36%, which is comparatively high. Somewhere between Labour in 1997 and 2001, two other landslides.

Indeed, in a YouGov poll asking why people were voting Labour only 28% of the respondents responded in a way that indicated support of the Labour Party or their policies:

- 5% – I agree with their policies

- 4% – To support the NHS

- 2% – For a fairer society

Compared to 69% indicating that they wanted to get rid of another party:

- 48% – To get the Tories out

- 13% – The country needs a change

- 4% – They are the best alternative with a chance of winning

Hardly a ringing endorsement of Labour and their policy agenda.

Turnout

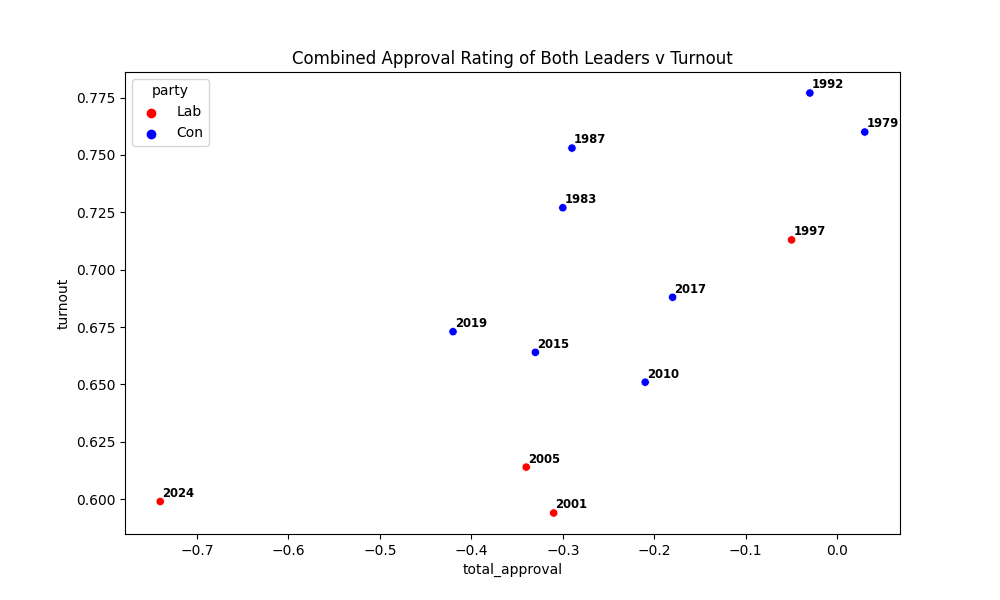

Turnout was very low at 60%. This low turnout may be driven by the unpopularity of the party leaders.

The data reveals a strong relationship between the popularity of the two major party leaders and turnout. The sum of the two party leaders net approval ratings is 62% correlated with turnout.

The sheer unpopularity of the two leaders is a clear historical outlier.

Why were the Conservatives so Unpopular

On to speculation. There are many reasons why the Conservatives are unpopular including well documented scandals. Rather than re-hashing these I will zero in on a few more structural things.

- They haven’t achieved anything – since the early days of Cameron there is little that the Tories can point at and say, this is what we’ve done

- Constant Infighting – 5 different prime ministers and a number of leadership contests while in power takes its toll. People do not want to vote for a party that is so divided and whose MPs are so obviously concerned with self-advancement

- Covid – a crisis of the scale of Covid has had a real impact on living standards. It also requires a lot of high stakes decisions to be made, some of these were mistakes at the time, some were mistakes in hindsight. In general however, the government will get judged asymmetrically with a failures weighted much more highly than successes

It would be tempting for a Conservative politician to blame Reform ‘splitting the vote’ for their defeat, but this would be an error. Their loss and Reform’s success was driven by the Conservative’s unpopularity. The vote was only split because people couldn’t bring themselves to vote for a divided party who has achieved little and been mired in scandal.

Therefore the Conservatives must resist the urge to lurch to the right to try and compete with Reform. A competent centre right party with a competent leader, untainted by the prior scandals and a sensible set of policies will do very well in five years time.

This is not 1997

Despite the landslide victory and the size of the majority this is not 1997. Labour, led by Starmer, is coming into power untainted by office but already unpopular. They also inherit a tight budget, struggling public services and an ever increasing pensions and NHS bill that will make the next 5 years very tricky.

From the data, this looks much more like Labour in 2005 than 1997 with the unknown being whether the Tories will successfully rehabilitate their image in opposition.